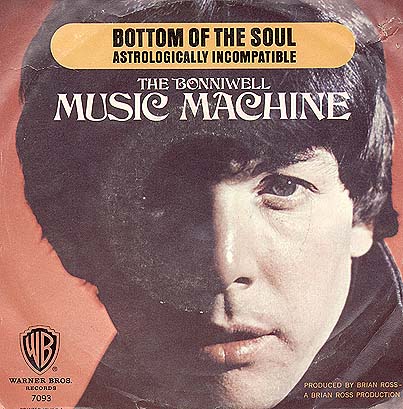

| THE BONNIWELL MUSIC MACHINE: BOTTOM OF THE SOUL

Research / Annotation

| |

|

Dedicated to On October 11, 2004 Sean Bonniwell described this page as "an exhaustive -- rarely seen -- discography of MM releases (some of which never were) Billboard ads, and the curious omission of Guerilla Garage (no doubt to be included posthumously)."

September 10, 1966

October 8, 1966

January 21, 1967

Warner Bros. - Seven Arts

October 24, 1969

September 5, 2022

March 6, 2020

Also

Shindig! Magazine

The Bonniwell Music Machine

If the universally praised, expanded edition of The Bonniwell Music Machine on Big Beat is rightfully regarded as the definitive version of the album then this reissue has to be considered an equally desirable artefact.

Rising Phoenix-like from the ashes of what would have been The Music Machine's second album, the change of name reflected the fact that this was essentially a solo project with Bonniwell completing what would be considered his magnum opus with the aid of session musicians. Though assembled in less than ideal circumstances and ultimately flopping on its 1968 release on Warner Bros, the resulting album, with Bonniwell's distinctively moody vocals, its mix of pop, garage, psych and even baroque influences offset with ambitious arrangements, endures as a bona fide garage-psych classic that comes packed with a succession of power-packed songs including the singles 'Double Yellow Line', 'The Eagle Never Hunts The Fly' and a whole lot more besides.

August 1, 2017

April 22, 2017

Misspelled *Discrepency* (5 Times)

April 22, 2017

March 30, 2018

December 21, 2016

The Music Machine

Produced For Release by Junichi Miyaji [Warner Music Japan]

April 16, 2016

2 x Purple Marble Vinyl LP

Light In The Attic Sean Bonniwell June 12, 2014

Double Yellow Line (2:10) Mono Released March 3, 2014

THE BONNIWELL MUSIC MACHINE

CD 01 (59:06)

CD 02 (63:00)

Single Review

Single Review

Single Review

Single Review

Single Review

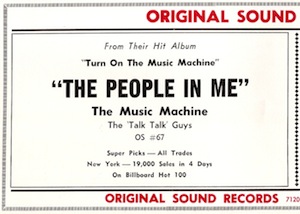

Ad

THE BONNIWELL MUSIC MACHINE

Two Page Ad

Single Review

Album Review

Warner Bros.-Seven Arts single

THE MUSIC MACHINE

Warner Bros.-Seven Arts single

Single Review

Single Review

Single Review

Single Review Released February 21, 2012

T.S. BONNIWELL

Where Am I To Go

THE CAPITOL DISC JOCKEY ALBUM

Released September 7, 2010

THE BONNIWELL MUSIC MACHINE

SIDE ONE:

SIDE TWO:

Sundazed / BeatRocket BR 121 Released November 12, 2007 (TURN ON) THE MUSIC MACHINE Repertoire REP 5094

Released September 4, 2006

THE MUSIC MACHINE 1966 - 1967

CD 01 (75:13)

Original Sound Mono 45 RPM Singles:

(Turn On) The Music Machine OSR LPS 8875 (Stereo):

CD 02 (52:08) Previously Unreleased (Mono)

THE BONNIWELL MUSIC MACHINE

ASTROLOGICALLY INCOMPATIBLE (2:31)

DISCREPANCY (2:29) Mono THE WAYFARERS Come Along With The Wayfarers N2PW-3369 Ticonderoga / The Wayfarers At The Hungry I "Folksinger" The Wayfarers At The World's Fair PPKM-4407 Crabs Walk Sideways / Most WAYFARERS producer THE RAGAMUFFINS Push, Don't Pull © June 11, 1965 The Day Today © July 29, 1965 High And Dry © July 29, 1965

I'll Take My Chances Much 'N' Much © July 29, 1965

Once And Once Was Twice She Tole Me So © July 29, 1965 Talk Me Down © July 29, 1965 Till The Roses Fall © July 29, 1965

What, What (Are You Serious?) Hubbub © October 5, 1965

Sufferin' Succotash

What's It To You?

Some Other Drum

OR 125 Talk Talk

OR 135 The People In Me Trouble © November 29, 1966

(Turn On) The Music Machine

Paris Song

OR 141 Double Yellow Line

OR 153 The Eagle Never Hunts The Fly

OR 167 Hey Joe

RCA March 15, 1967:

Astrologically Incompatible

The Day Today

Somethin' Hurtin' On Me Affirmative No

[ Talk Me Down ]

November 15, 1967: I've Loved You © February 16, 1968

The Bonniwell Music Machine

January 10, 1968:

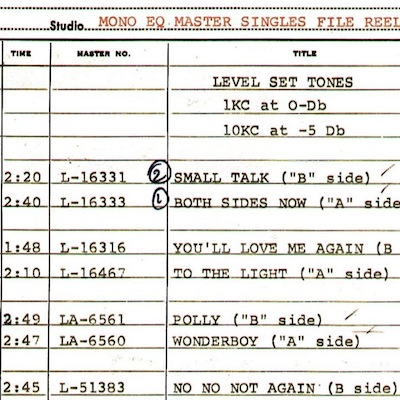

L 16467 To The Light

L 16643 Tin Can Beach

9048-BW Advise And Consent

U.S. Constitution Advise And Consent (Pulitzer Prize-Winning Novel) by Allen Drury (1959)

Advise & Consent (Film) Directed by Otto Preminger (June 1962)

Bell Single

Where Am I To Go

T.S. Bonniwell King Mixer © June 27, 1969 Dark White © June 27, 1969

ZEBRA:

THE FRIENDLY TORPEDOS:

OS 94 Gene West

Best Of The Music Machine Sean Bonniwell's

Sundazed CD SC 11030

Sundazed Sampler #2

Sundazed single S 131 Collectables CD 6044 (43:12) 1999 Sundazed CD SC 11038,

08. Talk Me Down © July 29, 1965

18. Point Of No Return

15. Worry (Instrumental)

01. Everything Is Everything Record Collector review September 2000 Sundazed LP 5038 Nuggets Nuggets 2/1. TALK TALK - The Music Machine 3/28. DOUBLE YELLOW LINE - The Music Machine

The Boston Globe

Think of the Beau Brummels from San Francisco, the Music Machine from Los

Angeles, Barry & the Remains from Boston, the Cryan Shames from Chicago, the

Amboy Dukes from Detroit, the Nazz from Philadelphia.

These are just a few of the bands represented on the new four-CD box

"Nuggets: Original Artyfacts from the Psychedelic Era, 1965-1968" on Rhino

Records. It's an expanded version of the original "Nuggets" disc released in

1972, which spawned the compilation/reissue craze so prevalent in retailing

today.

There was no shortage of American acts unashamedly jumping on the Beatles

bandwagon. "In 1964, when the Beatles came out, I saw exactly what was going to

happen," says Sean Bonniwell, singer with the Music Machine, which has two

songs on the "Nuggets" box: "Talk Talk" and "Double Yellow Line."

The Music Machine, however, became one of the most original garage-rock

groups of that time. The band rode the songwriting genius of Bonniwell, who was

ahead of his time in protest songs like "Eagle Never Hunts the Fly" (about

government hassling) and "Mother Nature, Father Earth" (about ecology). They

also had the technical genius of bassist Keith Olsen, who invented the

"fuzzbox," which created a trippy guitar sound that revolutionized the genre.

The group split up in 1969, but Olsen later became a prominent producer whose

chief credit was Fleetwood Mac's mega-platinum "Rumours" album.

Bonniwell, unfortunately, was not as lucky. Today, he lives in a garage on an

Arabian horse ranch in the small California town of Porterville (between

Bakersfield and Fresno). The garage has no running water (he does have access to

the main ranch house for that) and he's fighting legal battles to recoup his

song- writing royalties from the Music Machine's record label, Original Sound.

Clearly, the euphoria of the mid-'60s has given way to a harsher reality in

his case. "I'm just trying to survive," says Bonniwell, who is finishing an

autobiography, "Beyond the Garage," which he expects to put out by himself for

Christmas. (For more info, write to PO Box 409, Porterville, CA. 93258.)

Bonniwell is now a born-again Christian who is trying to deal with his anger

over his perceived mistreatment by his label. "The Lord says I must forgive my

enemies," he says.

He still sounds full of life, though, and is still writing songs. "I never

stopped writing," he notes, adding that he even has three albums' worth of

unrecorded material from the Music Machine days.

And what heady days those were, he recalls. The Music Machine once played 35

nights in a row. "You just threw everything in your VW bus and off you went," he

says. "We'd play almost anywhere, any time, but our resources were never

coordinated at all. That, and the fact that we rarely got paid. You couldn't

take a check from a promoter back then, because it would bounce. So I'd have a

big brown shopping bag and take the cash from the door."

Although the Music Machine had a druggy, psychedelic sound, Bonniwell says he

didn't do drugs and was "as straight as an ice cube tray." But the group was

radical in other ways. In order to stand out from the garage-rock pack, the

Music Machine dressed all in black, complete with dyed black hair and black

guitars, amps, and drums. They even wore a black leather glove on one hand (this

was long before Michael Jackson's single-glove look), all of which conspired to

get them into trouble when touring backwater spots in, say, the Deep South.

"I went into one place in the South and wanted to use the restroom,"

Bonniwell relates. "And this was still in the days when there was segregation.

The owner said, 'The white restroom is here, the black restroom is there, and

you ain't got one.' "

While many of the acts on the "Nuggets" box turned out to be one-hit wonders,

there's still a spirit that makes this one of the most essential collections to

any rock historian's library. The suggested retail price is not cheap ($ 59.98),

but it's a bargain considering there are nearly 30 songs per CD.

Turn on the Music Machine /

Beyond the Garage. The Bonniwell Music Machine. Compact disc. Sundazed SC 11030 (P.O. Box 85, Coxsackie NY 12054), 1995. Recorded 1967-1968. Produced by Brian Ross and Sean Bonniwell. Reissue produced by Bob Irwin and Sean Bonniwell.

The Music Machine's "Talk Talk" was probably the most uncompromising single heard on Top 40 radio in 1966. Lead singer and songwriter Sean Bonniwell growls like a misfit from Mars. The chord change leading into the bridge is audacious and unheard-of. The entire song is pure, ugly wallop. Unfortunately, "Talk Talk" was only a minor hit nationally. Worse still, the Music Machine became a one-hit wonder, which means that relatively few people have heard the marvelous body of work that fleshes out the promise of "Talk Talk."

That is a situation that can now be remedied, thanks to the release of these two CDs, which comprise almost the entire Music Machine catalogue (only a few cuts are missing, and these oversights are avenged by the release of several previously unissued tracks). What is revealed in these recordings is the genius of Sean Bonniwell-a true American original.

Bonniwell has an amazing voice. The closest points of comparison are Eric Burdon, Tom Jones, and Scott McKenzie-as bizarre as that combination may seem. Bonniwell shifts effortlessly from punk screaming to smooth ballad stylings. His pitch range is incredible. He is a brilliant singer.

On top of that, he has a unique personal vision, which guides his songwriting. Beyond the Garage consists entirely of original material and is full of should-have-been hits. Bonniwell's best recordings are almost impossible to describe. "The Eagle Never Hunts the Fly," a favorite of mine, is both chaotic and tightly structured. The arrangement is noisy and unrelenting, but richly textured in its own way. The words are about ecology, predation, and (probably) love, mixed together angrily and sarcastically. This is a frightening, devastating record.

Turn On unfortunately includes five cover versions, which are adequate but much less interesting than Bonniwell's original songs. "Taxman," "See See Rider," and "Hey Joe" are the worthiest covers, with the latter being both slow (a half year before Jimi Hendrix) and operatic (!). Turn On also features "Talk Talk" and its excellent followup, "The People in Me."

"Punk" that he is, Bonniwell is no snot-nosed sniveler. His approach is entirely adult, and his songs are for adults. This may be why commercial success mostly eluded him. You hear that Vox/Farfisa organ sound and expect bubblegum. What you get instead is mature psychodrama. Expecting a nasal, tenor "Come on down to my boat, baby," you get a throaty baritone, singing: "Come on in and show the world the soul you've never had, and tear away from dreams unborn. Shed the cage that makes you sad. Come on in. Don't cry no more. Come on in . .and close the door." (Another interesting comparison is the Monkees' curiously upbeat protest song "Pleasant Valley Sunday" vs. Bonniwell's much darker "In My Neighborhood," which covers the same subject.) The Music Machine had a commercial "sound" but were not juvenile or trivial enough for their own good at the time. That 1960s misfortune makes their work all the more listenable now.

Excellent musicians rounded out the Music Machine, and arrangement and production also shine in these recordings (except that the stereo mixes are generally primitive and often annoying). One odd fact that strikes me as I listen to the Music Machine now is that they knew exactly how to use a tambourine. But that is only the least of their charms. More importantly, the Music Machine pioneered punk rock while remaining a multidimensional band that also excelled at ballads, blue-eyed soul, and even dixieland flavorings. Bonniwell's visions and dreams took him far "beyond the garage" to create a great panorama of American music. His songs deserve to be heard.

The packaging of Beyond the Garage lives up to the usual high standards of Sundazed Records, with original liner notes plus several additional pages (including reflections by Bonniwell). Turn On is a barebones reissue with no new songs or liner notes-too bad it was not a Sundazed project.

Bonniwell has also written a touching and fascinating "autobiographical novel," called Talk Talk. It is available from Christian Vision Publishing, PO. Box 409, Porterville CA 93258.

THE RAW SOUNDS OF PROTOPUNK

Band: The Music Machine . Personnel: (original lineup) Sean Bonniwell , vocals, songwriting and guitar; Ron Edgar, drums; Keith Olsen, bass; Doug Rhodes, organ; Mark Landon, lead guitar. Record: "Best of the Music Machine ," Rhino Records. History: Caught up in the swirling excitement of soon-to-peak psychedelia, various American "garage bands"-several from Los Angeles-began to experiment in late '66 and early '67 with a brash, raw sound that would later be termed "protopunk." Among them: Seeds, Standells and Music Machine . Inspired by English bands like the Yardbirds and the Who, these U.S. outfits discharged what might be called aggressive confusion, swinging their chief weapon-the chain-saw buzz of fuzztone guitar-at enemies both real and imagined. "Talk Talk" was Music Machine 's only big hit, but one that expressed the raging style with a fury exceeded at the time perhaps only by Love's "Seven and Seven Is." The band's subsequent recordings for the Original Sound and Bell labels achieved little more than regional success. There was only one album, "Turn On." In late '67, members began to drop out, including Olsen, who began a production career that led to albums with Fleetwood Mac and Pat Benatar. Bonniwell kept MM going two more years, then tried a solo turn with little luck. Sound: Psycho-rock at its finest and progenitor of such modern songs as "Institutionalized" by Suicidal Tendencies, "Talk Talk" has a charged-up, manic urgency that still delivers a punch. It's hard to believe that a band able to wax something that powerful faded, but this smart compilation of singles, album cuts and four unreleased tracks shows that Bonniwell was never able to write anything quite comparable. Rockers like "Absolutely Positively" and "The People in Me" skillfully emit neurotic vibes but fall short of the hit's musical drive and vocal tautness. Still, several songs have a semi-naive, garage-psychedelic charm and considerable energy, and the album ends with two unreleased cuts from 1969 that indicate the group was getting the knack for newly evocative, moody material just before it broke up. Studio Sound

From the Summer of Love to the Winter of Content, Keith Olsen has balanced

technical suss with musical sensibility and produced some classic recordings.

Dan Daley shares his view of the changing ages.

SOMETHING SEEMS to happen to people from colder climes when they get to LA.

Something about the palm trees, perhaps, which are as non- indigenous to

Southern California as most of the people who live there. More likely, it's the

weather. It's manifest in a physical and intellectual freedom that comes with

the knowledge that you will never be shut in again by 7-foot snow drifts-the

kind commonly found on the plains around Sioux Falls, South Dakota, where Keith

Olsen was born.

After growing up in the equally frigid environs of Wayzata, Minnesota, Olsen

attended the University of Minnesota where he got hooked up as the bass player

with a few local bands, one of which, as he puts it, 'dumped me off in

California in the late 1960s'.

It was a fortuitous dumping, indeed, for Olsen went on to become one of the

seminal producers of radio rock in the 1970s and 1980s. His oeuvre is

prodigious-Fleetwood Mac, Eddie Money, Emerson, Lake & Palmer, REO Speedwagon,

Rick Springfield, Starship, Heart, Joe Walsh, Stevie Nicks, Whitesnake, Kim

Carnes, Sammy Hagar, Santana, Pat Benatar, Foreigner and the Grateful Dead. See

what getting out of the snow can do?

But how did one transition from journeyman musician to the other side of the

glass? In a sense, how did one not, back in the days of the Summer of Love. 'A

producer in those days was a guy who used to tell you how good your take was,'

says Olsen, sitting in his publisher's office in Nashville, where he is working

on getting this town to open up its catalogue coffers for material to work on

his next project, multichannel surround mixes for Olsen's KORE Group Records.

But more on that later.

After an introduction to production from the late Kurt Baetchler, who

produced the Association's classics 'Cherish' and 'Along Comes Mary', Olsen

helped form the Music Machine whose radio hit 'Talk Talk' got Olsen on the road

again, but at a higher level, and kept him tangentially tied to the evolving LA

music loop. Upon his return to LA, he was ready to take a shot at his own

productions, but first, he recalls, he realised that, as the equipment of

recording was evolving so quickly, he needed to spruce up his technical chops.

'I had enough electronic training in college to know what's going on

underneath the desk and enough music training to know what should be going on on

the other side of the glass. And then these good opportunities to go start

working with some bands started coming in-this was around 1971. But even though

I had learned the musical palette, I needed to know more about engineering. So I

hooked up with Gary Paxton's studio in his garage, then with Sound City in the

Valley. The board was a couple of equalisers, an old mixer and some wire

switches. I think it was a 3-track machine, then a 4-track, a Scully. But I was

learning the ropes and meeting people. I met Brian Wilson at his house just

after the Beach Boys had done Smiley Smile. And he was a little outside even

then. But I learned from him to envision everything about a production as you

hear the song the first time. You've got to see the whole picture, and get to

the point where you can see and hear where everything should be. It takes a

while to learn how to do that.

'I also learned that when you get into the studio, you have to be able to

modify your vision. But from the very beginning I learned that I always wanted

to be prepared when I walked into a recording studio.'

The engineering experience he gained was critical to the success of future

productions, enabling him to become a producer in a more traditional

manner-switching chairs in the middle of a recording session when Jerry Wexler

gave him the green light to finish Mac Rebenack's Dr John's Gumbo record in

1972. The credit opened the door for Olsen to hang out his producer's shingle.

The first act he worked with was Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks before they

assisted Fleetwood Mac into its pop phase. Both the music and the technology

were about to emerge from their respective incubators at the same time, with a

synchronicity that was perfectly timed for Olsen and his innate pop

sensibilities.

'The technology was starting to get better,' he remembers. 'The consoles,

the microphones could all take ever-higher SPL levels, so we weren't distorting

the preamps every time the snare drum hit.

'For a while I had been doing a bunch of weird acts-the Grateful Dead and

The Sons of Champlain-real San Francisco acts. I did Terrapin Station with the

Dead. I was really learning to be a producer working with acts like that.

'Terrapin Station was an album that we worked on for four weeks before we

got our first basic track. Speaking of envisioning a record before it starts-I

was looking to hear something tight-sounding, and I picked the wrong band to do

that with (drummer) Mickey Hart played on top of the beat and (percussionist)

Bill Kreutzmann played behind it, so everything sounded like a flam. After about

a week of that, I suggested the possibility of orchestrating the drum parts to

Jerry (Garcia). And Jerry says, "Sure, man, see you later," and walks out. His

way of saying, "Just go ahead and do it". So I had Kreutzmann be the kit player

and Hart as the percussionist, cause he's the fire anyway. And it worked.

Instead of having two drummers playing against each other, we had a little

groove thing going.'

It wasn't enough to get the Dead big radio hits-that would have to wait

another 15 years for 'I Will Survive'. But the lugubriousness of the San

Francisco music that was coming to LA to record was a useful learning tank for

Olsen as pop music and recording technology were about to join forces and put

corporate rock on the map in a big way. On Foreigner's 1978 Double Vision album,

Olsen was looking for new ways to cut guitar sounds and stumbled onto the notion

of using the inherent fuzziness of wireless systems when guitarist Mick Jones

showed a predilection for staying in the control room while playing at New

York's Atlantic Studios.

'The long cables running from the control room to the studio were taking the

top off the sound,' Olsen says. 'We didn't have amazing cabling then like we do

now. It was more like zip cord. But the gain from the transmitter on the

wireless gave us a little more input power, and that gave us back a very cool

top end. The amps were set up in the studio in a corner-when you corner-load the

cabinets you get a really great bottom end out of them. And we miked them with

some kind of Shure mics-that was about all we had for high SPL mics back then.

And we used the room for natural reverb with some mics placed relatively close

around the amp as well as right on the speakers.

'For the drums, I built a riser with cinder blocks from a construction site

and thick plywood on top-there was no ring to the drum sound any more. The drums

had snap and power. Combined with the angle of the mics on the drums, we had

eliminated the ringiness of the kit. I had figured out part of that when I was

working with Fleetwood Mac; their drum sound was so tight because the room was

so dead. I had been experimenting with recording in more live environments, but

I found that if you had a real live environment you get so much destructive

interference from reflections that you get a real roomy drum sound but you don't

really get any of the power, the snap, punch and crack.

'On Lou's vocals, I used a technique that I had been using since Buckingham

Nicks days, processing similar to what George Martin had used with the Beatles.

I took a Dolby noise reduction card and started clipping the odd bit off, a

transistor or two. You then out the card on the encode side instead of a

compressor. Use it as an expander-it's level-sensitive and band-sensitive, and

all of a sudden you have this really tight and airy vocal sound without having

to go through intense amounts of EQ or compression. I don't think the Dolby

people liked me for using their stuff that way.'

Like it or not, Olsen was looking to create the sound in the tracks, not in

the mix-a classic approach in the days before remixers had even been heard of,

and one that helped define the radio sound of the day.

'You learn about spectrum mixing-not putting everything into the same EQ

area. I was layering things, but I was also using the musical arrangements to

get the sound together. Not so much using EQ, but arrangement. The one thing I

learned was, remember the source-where the music comes from. Great words to live

by, because all the gear in the world cannot make a bad guitar player play

great. I also didn't like leaving things until the very end in the mix. I liked

to put it together the way I heard it the first time in my head. If the artist

is fine with that, then everything's moving ahead, but if not, then you have to

try things a few different ways and the mixes get a little more hairy because

you're then trying to take two visions and put them together. That can make for

a difficult mix.'

One that wasn't difficult was Rick Springfield's classic 'Jessie's Girl'.

'Here you had a soap opera star who was actually a very creative, musical

guy. He was very inexperienced in the studio but we had the basics cut for that

track in one day by 4 o'clock. Bing, bang, done. That's how records were often

done in those days. Looking back, it was remarkably fast.'

Then there were the ones that didn't go quite as smoothly. Preparing for the

follow-up to Whitesnake's hugely successful Slide It In in 1987, lead singer and

band leader David Coverdale had been working with another producer at Compass

Point Studios in the Bahamas. But Coverdale was hung up on the vocals, and he

and cowriter John Sykes called Olsen in mid-way through the project.

'He calls me and sends me the tapes and I realised that the problem was that

David couldn't sing in tune because every guitar and bass track on the record

was, shall we say, outside the window of acceptability, pitch-wise. They had

printed a lot of effects like harmonisers and somebody went a little bit

overboard with the outboard. They were going for a sound, but they weren't

looking at the big picture. If you can't tune to it, you can't overdub or sing

to it. So I had to go in and rebuild, taking tracks that were half of stereo

tracks, but which had less effects on them and put them together to form new

tracks. We were looking for things that could pitch references. And the drums

were also a bit off timing. I and engineer Brian Foracker was using two machines

to do punch-ins and fly around, and offset the beats. I built a 32- track

digital master out of all of these analogue tapes. It took a month, but it gave

us workable tracks for the album. That and a few new overdubs with guitarist

Dann Huff. Then I called David and I said "I think it's time for you to sing

now". He came down and on the first day we punched play and I started him off

with an easy one, which turned out to be "Still Of The Night". So it worked out

quite well in the end.'

So did a few others, including Heart's 'Passionworks', REO Speedwagon's

'Here With Me' and Pat Benatar's 'Precious Time', not to mention Fleetwood Mac's

'Rhiannon' and 'Over My Head', which took the band's eponymously named first

album to 9 million in sales.

Olsen has a new project now, based on a new technology. DVD offers over 9Gb

of storage capacity, which makes the Red Book CD look like a piker, indeed, with

its barely 650Mb of data. While name-brand technology has never held any

particular allure for Olsen-his 20-year-old personal studio, Goodnight LA, is

fitted with a 96-input Trident Di-an console, and of which he laughs, 'I'm the

only man in the world using one on a semi-regular basis'-DVD holds some business

potential that he finds irresistible.

The rapid growth of home theatre: over 10 million US households have some

type of surround-sound system, and another 23 million are equipped with Dolby's

Pro Logic matrix surround. This has opened the possibility of delivering

surround music mixes on DVD, and a truncated matrixed version on CD, the

latter of which Olsen started doing last year with the formation of the KORE

Group record labels. The latter of these he is gearing up for as the new disc

technology slowly, but inexorably comes on line. Two new artists, one in jazz

and one in new age, and two sampler discs of remixed material, have been

compiled thus far.

'The idea is feasible and viable technologically,' says Olsen. 'We needed to

see if it was also feasible and viable in the market. If the market was there

for surround mixed music. Twenty-five million people go down to the video store

twice a week, get a video, stick it into their surround-sound home theatres and

for 96 minutes they sit there and get whacked by surround-sound effects. Then

they turn off their VCRs and if by chance they have left the Pro Logic decoder

on when they put in a CD, the centre collapses on the sound. It doesn't work. So

I say, why don't we make the mix an event? Make it an experience to listen to

music again. So we started mixing a few things I had in the vault and a few

things friends gave me-Tom Petty, Stevie Nicks. I mixed that in surround sound

keeping the artistic intent of the original mix in mind-remember what I said,

remember the source? The same tone and the same placement of instruments, but

everything else just spreading around you.'

What is the secret to mixing in 5.1 versus stereo? 'The thing in surround mixing in general is not how much you do, but how

much you don't do,' cautions Olsen. 'That seems to be the secret. You use

effects in a different way. You don't want to load up the front of the mix with

effects; you can use them in the rear channels.'

Olsen gives an example of a Pro Logic 4-channel mix: 'We place the guitars

left and right, we put the drums kind of spread out among all three front

channels, then move them in just a little bit so it doesn't become all kick and

snare. The bass (guitar) is mostly in the centre. The lead vocal? Well, gee,

there's a band here, so let's have the lead vocalist take two steps forward

towards you, like he is on stage. Then you take a bit of the vocal or its

effects and put it behind you to achieve that. Put that into the surround and

all of a sudden the vocal is in front of the band, but still part of it. But

there are delays on these home systems and people screw with them, so you have

to be careful about not placing things too far out and moving them around like

crazy. Don't go crazy because it makes people nauseous to the point where they

don't want to listen to it. There's the potential for high listener fatigue in

surround mixing. The Dolby Pro Logic system gave this a lot of thought because

it's also compatible to stereo and to mono, which is very handy for this

market.'

The KORE Group's plan is to license existing masters, remix them for

surround, and rerelease them, using a variety of direct mail and retail outlets.

The project started three years ago and pulled Olsen out of the production

loop-voluntarily, he says.

'I took three years out of my life to figure the surround thing out. And I'm

not going to do anything else until I figure the business side out because I

think this thing is going to be massive. In 1998, GM, Ford, Toyota and Mazda are

supposed to be coming out with surround systems in their cars, so that's really

going to open the door. DVD is still a buzzword for the next six years or so,

but it'll be there, too. To paraphrase Jerry Garcia, it's been a long, strange

trip. But I like where it's going.'

Sleeve notes: The Best of the Music Machine

'It gives us great pleasure to finally make available a consummate package

by one of the best rock bands to emerge from the mid 1960s. Because of their

aggressive attack and dress-all black, including dyed hair and black glove on

one hand only-the group was placed in the vanguard of the punk rock boom. But

the Music Machine was much more than that.

'Songwriter Sean Bonniwell assumed various provocative stances and

propelled his men through a series of successful experiments, unusual approaches

to tuning, use of cymbals, bass emphasis, electronic guitar sounds, an early

version of the fuzz box created by bassist (now producer) Keith Olsen, all aided

by the production team consisting of Brian Ross, the producer, and Paul Buff the

recording engineer. The latter, an electronic genius, invented a 10-track

recording machine during a time when most other advanced studios were struggling

with four tracks. The records of the Music Machine just might have been the most

state-of-the-art of their day.

'The group's very first single, "Talk Talk", provides a good example. An

intense whirlwind of disillusion, the song is based on a series of stops and

starts that Sean refers to as 'Chinese Jazz'. The only time the title is

mentioned is at the four beats at the very end. Right off the group forged its

own identity, characterised by fuzz guitar and Farfisa organ, swathed in an aura

of mystery. Sean sang and played guitar and wrote the songs. The rest of the

band consisted of Olsen, Mark London, lead guitar, Ron Edgar, drums, Doug

Rhodes, organ. This is the line-up that played on the Music Machine's better

known recordings. Although the group was popular in its native Los Angeles, and

while various singles achieved regional recognition, save for "Talk Talk" the

band's gems have been long waited to be rediscovered. That time has finally

arrived.' LOU CHRISTIE &

| |